Digital Navigators:

Connect to Opportunity

Digital navigators are all the more needed now as recovery efforts must include supporting millions of Americans to access information and services online.

To ensure our nation’s workforce has the digital skills needed for an equitable and sustained recovery

Digital navigators are all the more needed now as recovery efforts must include supporting millions of Americans to access information and services online.

The Digital Navigator program is “an adaptation of traditional digital inclusion programming.” Its goal is to ensure residents receive on-demand tech support and relevant information to secure internet access and devices, as well as the opportunity to build foundational digital skills, learning, and job training. This is done through providing much-needed just-in-time, one-to-one and small group dedicated support via phone service, email, text, video chat, and other communication methods that work for the learner-worker. Digital navigation services can also be provided in-person or in blended formats. The model is a solution to address both digital access as well as learning and upskilling, and at scale.

“To build a more equitable digital future as digital learning and services increasingly are the new normal, we must ensure that support for developing digital resilience is radically accessible to ALL of us.” – Priyanka Sharma at EdTech Center @ World Education and Digital US

With funding from Walmart, the EdTech Center @ World Education is working with some of its Digital US Coalition partners to develop new models for offering digital navigator services to help learner-workers connect to the internet, secure equipment, acquire foundational digital skills, and access upskilling and job opportunities. This initiative is identifying key features and best practices to facilitate the adoption and successful replication of models across the country.

The development and scaling of digital navigator services meet the immediate needs of learner-workers and their families, helping them find and apply for safety net services and to reskill or upskill to stay employed or find new work opportunities during the recession.

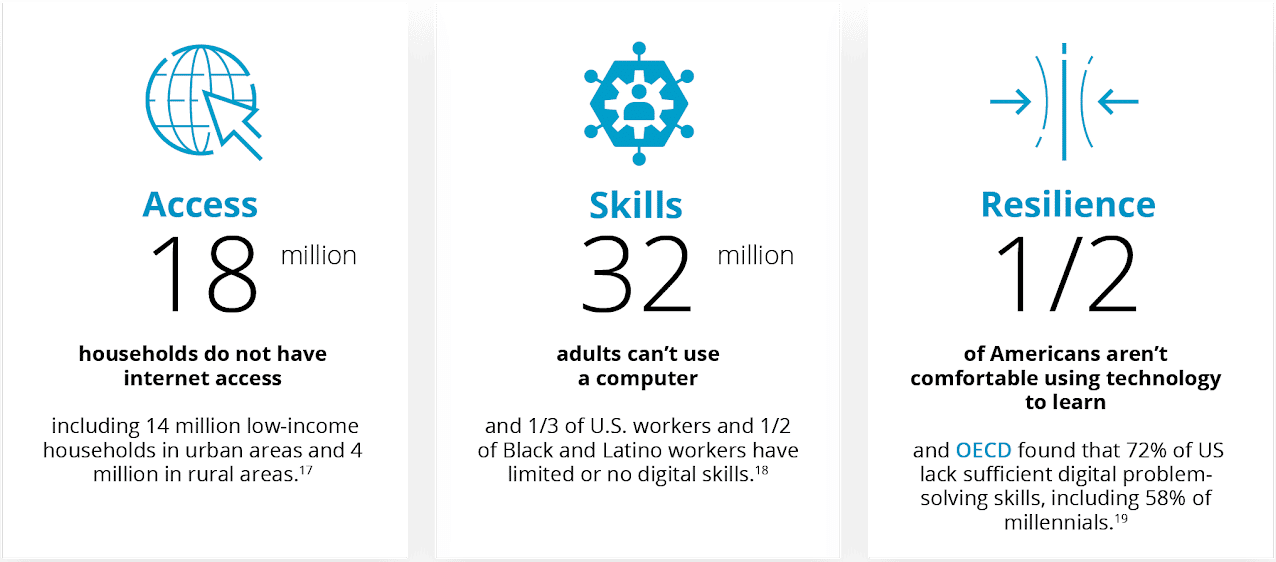

There is a great inequality that exists in our modern world — digital exclusion. Digital exclusion locks many people, particularly black and brown communities, out of opportunities, with considerable costs to them and our wider society. Digital exclusion refers to those who lack access to technology and foundational digital skills training.

Before the pandemic and since the early- to mid-1990s, digital inclusion programs have focused on improving digital skills through classroom training and public computer lab access through community technology centers/labs. Despite these efforts, the gap in digital skills remains.

In addition, the pandemic response has severely reduced libraries and other community organizations’ ability to offer their traditional digital inclusion programs. Face-to-face training classes, public access computer labs, and walk-in support services have been unavailable for several months or longer. As programs at libraries and community-serving organizations adapt to the new environment, the Digital Navigator model is being adopted and can become part of the services being offered going forward remotely or face-to-face.

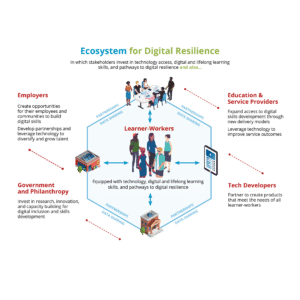

The social distancing measures needed to tackle the pandemic have put the digitally excluded in a precarious situation. Unable to attend community technology centers or education and training labs, many lack access to connectivity, digital devices, or the required digital skills to access essential services, which have rapidly moved online. At a time when technology innovation requires all of us to develop digital resilience, a lynchpin in developing a more equitable ecosystem for reskilling and upskilling to ensure economic recovery will be offering more accessible, just-in-time digital navigator services at scale.

The Digital Navigator model is a comprehensive model that addresses multiple layers of becoming digitally included, which traditional classes and other services in the past might not have addressed completely. In addition, the Digital Navigator model is appealing as it offers flexibility not only in terms of where, how, and when services are offered but also who provides the service. Digital Navigators can be trained staff or volunteers that help learner-workers (whether through phone, virtual hotlines, or at drop-in locations) secure affordable internet access, devices, and foundational training so they can meet their goals. Foundational digital skills can be offered directly or through referrals to learning programs that can help learner-workers upskill, access critical services, and search for or apply for a job.

A business or organization could embed digital navigator services into its HR and L&D departments to ensure that all its employees have personalized support to secure affordable access to the internet and devices and develop foundational skills to navigate online programs for learning and managing operations.

Examples of how the Digital Navigator model can be implemented include the work that NDIA is piloting with Rural LISC sites in Appalachia and Salt Lake City Public Library

The EdTech Center at World Education and Digital US are working with partners in California, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Washington DC, and South and North Dakota to pilot the model to institute Digital Navigator services in diverse contexts. National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA), a Digital US partner, is also piloting and supporting a digital navigator model with Rural LISC sites in Appalachia and Salt Lake City Public Library sites. In Philadelphia, three local organizations CLC, SEAMAAC, and DREXEL, received government grants to provide digital navigator services, and the model is now expanding citywide.

This toolkit serves as a high-level guide and offers a starting point for partners currently planning to pilot digital navigator services across the country. Our implementation is being informed by guidance from the Digital US members and our partners in the adult education and workforce development field. The project leadership continues to contribute to and learn from the Digital Navigator working group, coordinated by the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, and partially underwritten by Digital US. Members of the group can be found here. Highlighted in this document are contributions made by participants of the group.

This tool kit covers five important elements in program planning and design:

• Program Goal – What is this program interested in accomplishing? What problem is it intended to address? Who is the target population?

• Program Description – What activities will you be doing to achieve the desired program outcomes? What service(s) will you offer?

• Measurement and Evaluation – What does success look like, and how can we measure it? What metrics will your agency use to track results?

• Implementation Plan – Are there training and startup requirements? What current resources can you leverage and or will you need additional resources?

• Building a Digital Equity Ecosystem – Do you know potential partners offering complimentary, wrap-around, or supportive services? What strategic alliances with businesses, governments, and other organizations or institutions, can be made to ensure digital inclusion?

To develop an effective Digital Navigator plan, we need to understand and articulate the digital access and digital literacy needs of the community. To do so, draw on information about the general need for expanding the implementation of the Digital Navigator model mentioned in this guide. Then, make this relevant for your work by identifying the magnitude of the need for a Digital Navigator program in your community or program. For example, ask yourself (and others) questions like:

a. What is the number of students without reliable access to the internet in your district, or region?

b. How many learner-workers in your program only have mobile phone access, what is their level of digital literacy or comfort using technology?

c. What is their level of awareness, skills, agility, and confidence to be

empowered users of new technologies?

d. Is the need widespread, or are particular demographics areas of your community most in need of support to cross digital divides?

In addition to the worksheet created by Arizona State Library, this community tool box by the University of Kansas can help you determine need in your community.

Your program’s focus will depend on the community’s needs, organizational goals and priorities, and the capabilities and resources of your organization or community. The end goal of your program is to establish a Digital Navigator service that responds to the community’s needs and leverages the capabilities and resources.

Most Digital Navigator programs concentrate, at least initially, on providing information about low-cost internet access, devices, and tech support. However, there is an opportunity to use the model to provide foundational digital literacy skills and warm referrals to adult education and upskilling programs. The extent to which these additional supports are provided, and the strategies used to do so, will impact a program’s ability to build digital resilience in our communities.

Digital resilience signifies having the awareness, skills, agility, and confidence to be empowered users of new technologies and adapt to changing digital skill demands. Digital resilience improves capacity to problem-solve and upskill, navigate digital transformations, and be active participants in society and the economy.

Will Digital Navigators provide services to seniors, people with disabilities, learner-workers, residents of a specific zip code or neighborhood, youth, unemployed, underemployed, and dislocated people, immigrants, young women? Or is your program open to anyone calling your line?

It is important to define the group of people for whom you are designing the program. Identifying your target population will help you with recruitment, ensure services meet the needs, and help with retention efforts.

“At a library, Digital Navigators could be serving both general and specific audiences, sometimes at the same time. It just depends on their community and who asks for help, or if the library determines on its own to help a target group or offer programs to the general public.” Heidi Ziemer at Western New York Library Resources Council.

→ Demographic Characteristics – What demographic characteristics define the population you serve? What is the size, or how large is your target population? How many people in the category/categories identified will need your services? This informs the need for your program. The target demographic will also influence the kind of support requested, and as a result, the services and information digital navigators need, in order to help learner-workers achieve their goals.

→ Degree of Reach – How many people are you looking to serve? Realistically, what percentage of that population will your program be able to reach given available resources? This tells us why your program is important and how many people will be served.

→ Assets: Participants strengths and capacities – We tend to look at target populations from a deficit perspective. We often think of “them” as people lacking or not having something. However, it is important to identify and recognize the internal and external strengths of the people we work with. Internal assets can be things like commitment to learning and growth mindset, motivation, or positive attitudes about technology. External assets can be peer or family support systems, community bonds, etc.

→ Challenges – Just as important as identifying the assets is thinking about the challenges in reaching and retaining people in your program. For example, in working with homeless people, you can assume that they will have difficulties keeping an address or securing reliable contact information. Working with seniors may mean providing support to mitigate memory, eyesight and dexterity issues. In general, working with people who lack internet access and technology could mean a lack of exposure and unfamiliarity with jargon and terms commonly used by those who are more familiar with the technology. Thinking about the risks or barriers allows you to create strategies to counteract the challenges the target community faces and help you be more strategic and proactive about partnerships with agencies and organizations that can provide support or wrap-around services.

→ Program eligibility and other requirements – This goes hand in hand with the target population you identified. For example, you may restrict services to people that belong to a determined program (public housing development, etc.), age bracket, or geographic area (of the city, urban or rural areas, etc.) Other categories may include unemployed, attending an adult education program, single parents, returning citizens, etc. Are there additional requirements for your program? (benefit recipients, legal status, etc.).

The Nebraska Library Commission developed a target audience guide that can be helpful to identify Audience & Assess Resources.

Digital Navigators services could include:

Digital Navigators can be the first step to get internet access, equipment or receive quick technical assistance. They can also be a one-stop service center making referrals to programs and facilitating enrollment in virtual digital literacy classes, workshops, and upskilling opportunities.

→ How often and how frequently will services be offered?

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

→ What are your service hours?

The answer to this question may depend on the number of trained staff or volunteers you have, the needs of the population you seek to serve, and the number of phone lines and equipment available. All of these will impact the service you can offer.

The goal of the digital navigator is not only to provide accurate information about equipment, connectivity, or foundational education options but to offer support that addresses the particular needs and goals of learner-workers receiving the service.

To effectively address learner-worker needs, digital navigators need to be familiar with technology, be willing to learn new tools, have up-to-date information about connectivity and equipment, be familiar with resources available in the community and need to be culturally competent. Being culturally competent means having the ability to understand, communicate with, and effectively interact with people across cultures and who may follow different norms and traditions, perceive, think, interact, behave, speak, have physical conditions different from your own.

→ Support for people with disabilities – Assistive technology (AT) is equipment or software used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of persons with disabilities. Digital Navigators should be familiar with basic tools to enhance communication and access, and have available resources at hand with information to provide learner-workers. Helpful information is provided by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, also helpful are these guides created by Temple Institute on Disabilities.

→ Language access services – Language access allows English Language Learners (ELL) individuals access to a wide range of services. A ELL person does not speak English as their primary language and is yet developing proficiency with reading, speaking, writing, or understanding English. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 21 percent of the U.S. population speaks a language other than English. Of that percentage, more than 40 percent speak English less than “very well.”

Newly arrived immigrants are some of the most vulnerable in society and often need support settling in and connecting to information about local services and jobs. However, these groups are often thought to be digitally, linguistically and culturally excluded, and the move by governments and agencies to online platforms could exacerbate existing barriers to accessing public services. Furthermore, these groups may lack the necessary digital skills and host-country language ability to take full advantage of digital services available.

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

What protocols will you set in place to identify and redirect these calls to bilingual interpreters?

Your plan should address and set procedures for:

The Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles’ Language Access Procedure Manual has practical instructions for staff that work with clients. It includes step-by-step processes for walk-ins, call-ins, and verbal and written communications. For more information and resources, go here

→ Plain Language

Also important is to acknowledge that those seeking services may have low literacy skills. This means that any printed material should use plain language to ensure people can access this information.

“Research with refugees suggested that focused instruction on the vocabulary of technology terms supported success on Northstar Digital Literacy tests and supported learner engagement because it gave them the language they could use to ask questions and understand instructions. ” – Jen Vanek at EdTech Center, World Education

In sharing information about technology, you should also be aware of jargon. Avoiding jargon altogether in digital navigation can be difficult. However, it is important to acknowledge the fact that using technical terms may be a barrier for effective navigation. You can find more information and tips to avoid jargon at plainlanguage.gov.

One of the challenges you may face is reaching out to those that need this service the most. In general, these are the people that do not have internet access or equipment, and as a result, traditional online channels may not reach them. The pandemic also restricts face-to-face interaction. Thinking about ways to ensure the communities that need it most know about your services is key.

In general, campaigns must communicate “why I should participate,” “where I can get trained,” “how will this help my family,” and “how can these tools help me at work and in my life”

What communication channels do you have available, or which do you need to create? What communication channels are currently used and trusted in the community? Relying on social media may not give the results you seek, especially if you are trying to reach emergent users of technology who are not yet users of social media.

Reaching out to schools, youth organizations, food pantries may be a better way to reach the target population. Create partnerships with local community groups, churches, etc. who can help get the word out -even through text if they have contact info for people. Also, studying media sources used by the target population -like the local convenience store, tv, radio or their local newspaper, as well as local barbershops- is advisable. For “hard-to-reach” communities, a strategy worth considering is engaging community outreach advisors or community outreach ambassadors. They are members of the target community, and as such have valuable social networks and are trusted messengers in the community.

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

For examples of what organizations are doing visit: Community Learning Center, Drexel ExCITe Program, SEAMAAC, Chicago Public Schools and Connect Arizona; or use this template to help you create a communications strategy to guide your outreach for new students.

These are the fundamental norms, rules, and values that guide the program (e.g., being inclusive, client-focused, etc.). These principles should be part of the training of Digital Navigators and be embedded in your program’s activities from the way calls are answered to the way services are offered, and the way referrals are made.

The way you interact with callers can be an important recruitment and retention tool. Most times, callers satisfied with the experience, will tell friends and family to contact you to get assistance. The experience also influences the likelihood of participants to seek more services, participate in other training activities, complete training, and achieve goals. Don’t underestimate the importance of quality service in attracting new learner-workers to your program and to further engage in services.

While testing or implementing the program, it is important to learn what’s working well and what isn’t. A data collection strategy is key here. A sound data collection system will let the people you serve, your partners, and the community, in general, know the outcomes of your work.

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

“Consider scheduling weekly or biweekly calls with Digital Navigators to share success, challenges and to brainstorm solutions ” – Karisa Tashjian at Digitunity

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

A suggested intake form can be found here. Here is another sample intake form created by SEAMAAC in Philadelphia.

It is important to identify the assets that exist in your community and build a database or directory with information that can be used to help people get the services, devices, information, as well as the digital skills and job training they need.

Planning needs should be driven by exploration or reflection that covers the following questions:

→ Digital Learning Curriculum – In addition to identifying equipment needs and assets in your community, you also want to identify digital learning curriculum. SkillBase provides relevant material and valuable learning resources. You can find more here. Diverse organizations and employers, both big and small, would benefit greatly from national sharing of research and best practices in instruction and assessment in developing both essential technology skills and digital resilience.

| Needs | Who provides? | Cost |

| EQUIPMENT

Telephone lines Internet Desktop/ laptops/ tablets/ smartphones Training materials (handouts, videos, digital resources) |

||

| HUMAN RESOURCES

Paid Staff A coordinator Volunteers (bilingual staff and volunteers) Training |

||

| MONITORING AND EVALUATION

Free or paid Database Data entry Creating reports Tally request for services Collecting successful stories |

||

| MARKETING

Social media Website Local newspaper Translation services |

It could be embedded into an existing community institution or an established organization, like a library, a housing authority, school, a retail store, laundromat, or a social service agency; or it could support another program agenda, like workforce training, adult literacy, health services, financial literacy, public childhood education, or some other kind of existing program. If the answer is “standalone community Digital Navigator program,” then who’s the “owner”? Is there a sponsoring organization in place?

“This is where we inspire people to be creative. Digital Navigator services can be provided in diverse locations around the community to make services more accessible -laundromats, DVM, retail stores, barbershops, etc.” – Alison Ascher Webber at EdTech Center at World Education and Digital US

This will depend on the needs of the program and the expenses associated with it. What aspects can be sponsored by a partner organization? What data do you need to capture impact for continued sustainability?

Professionals, educators, trained staff, or trained volunteers? How would you recruit? What characteristics do they need to have? What skills do they need? How would you provide the training required?

Digital Navigators are trained staff or volunteers that help learner-workers (whether through phone or virtual hotlines or at drop-in locations) secure affordable internet access and/or devices and learn to use them to help meet their goals, such as to find and use an online learning program to reskill, to access critical services, or search for or apply for a job. The Digital Navigator works from home, or when social distancing is not necessary, they will work from an office or facility in group settings. This program can also be adapted for house calls and site visits.

If working from home, they will need a dedicated phone line, headset, internet subscription, and computer. Interactions happen by phone, video phone, and additionally via remote desktop once the client is online.

→ Digital Navigator Responsibilities:

The Digital Navigator acts as a liaison, providing individualized or small group assistance regarding connectivity services information, devices and foundational digital skills. The Digital Navigator educates learner-workers so they can make their own decisions, resolving any emerging problems that learner-workers might face with accuracy and efficiency. This assistance is provided primarily by voice telephone but may also include in-person, email, text, video chat, and other communication methods that work for the learner.

More specifically, a Digital Navigator will

To access the Digital Navigator Resource Hub, click here.

→ Digital Navigator profile:

A competent Digital Navigator:

→ Digital Navigator Job Description

To help stakeholders, the NDIA has developed a baseline job description for staffers to do Digital Navigator work that can be tailored to meet local needs. Sample job descriptions from TLC Philly and Digital US are also available.

→ Digital Navigator skills and competencies and Training needs

A Navigator’s professional training will include:

Click here to access the Digital Navigator Training Guide that can be customized to your needs. For more information, please contact Priyanka Sharma at priyanka_sharma@worlded.org

→ Volunteer Recruitment

Digital Navigators can be full or part-time staff or volunteers. For more information on how to establish a volunteer program at your organization, see this guide. This article from NTEN also provides good information. Another good source of information is VolunteerMatch; you can find a list of webinars related to volunteer management here.

Universities can be a good way to recruit volunteers. Immigrant advocacy agencies can also help you recruit bilingual volunteers able to provide services in the languages spoken in your community.

A volunteer job description with specific time commitments, will set the expectations clear from the beginning. Volunteers can be and often are highly committed individuals, but they need clarity and support. Connecting them with callers soon after training is important to keep them motivated.

As mentioned earlier, programs might address only one or two of the elements of digital inclusion. As a result, collaboration within organizations is fundamental to help community members be fully connected.

In building this ecosystem, it is important to consider how the people you serve will be able to access all of the elements of digital inclusion (affordable connectivity, affordable devices, digital literacy skills, or tech support). Do you know potential partners offering complementary, wrap-around or supportive services? What strategic alliances with businesses, governments, and other organizations or institutions, can be made to ensure digital inclusion? Also, consider whether your program might duplicate or even compete with existing community efforts.

A successful strategy requires building innovative partnerships. Alliances among government, private sector, philanthropic and community leaders, adult education and workforce organizations, libraries, and other systems need to participate in order to ensure no citizen is left out.

Some important actors to consider are:

Senior city officials, technology players in the community, advocates/representatives of underserved citizens, economic development agencies, health care providers, immigrant advocacy organizations, legal agencies and clinics, financial sector players, chambers of commerce and entrepreneurs, school system members, public library system leaders, academics, not-for-profit executive directors (technology centers), foundation executives, among others.

More ideas can also be found on this Coalition Guidebook developed by NDIA. This white paper from Power Up: The Campaign for Digital Inclusion also offers relevant information.

The Community of Practice (CoP) is a professional learning space. This community is a place where programs, partners, and practitioners can seek help from peers, collaborate, network, share knowledge and resources, identify and share best practices in implementing Digital Navigator models in diverse contexts and communities.

→ Guiding principles of this community of practice:

Vision: This community of practice exists to ensure that every resident of our community has home internet access, basic equipment and technical support, and foundational skills to access information and resources to improve themselves, their families, and their communities.

Mission: We work together to promote the recruitment, training, deployment, and effective use of the Digital Navigator model to address digital inclusion needs in multiple settings, organizations, and communities. We exist to advocate for universal, affordable broadband access and basic digital literacy and/or upskilling through coordinated public and community initiatives.

Objectives: We share experiences, challenges, and best practices in piloting Digital Navigation efforts across the country. We share resources and collectively learn and identify best practices for future implementations. We promote programs that utilize Digital Navigators as a strategy to secure and expand equitable internet access, digital literacy, and digital inclusion. We share resources and experiences to improve our practice and to expand the Digital Navigator model.

JoRena, a learner at the Sitting Bull College, didn’t know much about the basics of a computer until she started working with the Digital Navigators at the GED program at Sitting Bull College. “Coming to the GED program as a student and working with a computer, I have learned so much. I now know how to organize files, use email and schedule using the data and template apps. I am very grateful for the GED program, the digital navigators, and all that I have learned!”

JoRena, Sitting Bull College

A learner at JVS Boston

Luisa joined the JVS EfA (English for Advancement) program in April 2020 to learn English and advance her career as a CNA (Certified Nursing Assistant). However, Luisa lacked the equipment she needed to successfully participate in classes. Thanks to the TAP team she was able to get a laptop just in time to start her classes. Louisa successfully completed the assessment over the phone and enrolled in the online Caring for Our Seniors Training Program in Jan 2021. She will be graduating this month!

Lottie is a learner at a Literacy Minnesota-run learning center. She needed help understanding how to find, open, and manage her multiple email accounts, some of which she used for school purposes, and some of which she used to connect with her family. The digital navigator spent one-on-one time with her on digital literacy instruction around this topic. She can now easily find emails from her instructor, making her a more effective learner, as well as stay in better contact with her loved ones.

Laptop dropoff, JVS Boston

Ajani and Neela are experienced civil engineers from Ethiopia who were recently granted asylum and are looking for jobs in their field in the US. They are enrolled in the JVS Together We Rise program which supports Boston area refugees to access career development, training, and higher education opportunities. In the meantime, they are eager to continue gaining technical skills to make their applications more competitive. Neela and Ajani found a free online training in cartography using ArcGIS Pro software and signed up (training is provided by Esri, the company that makes the software). JVS was able to issue them a laptop through the TAP program, allowing them to download the trial version of the software and participate in the training. They are excited to be gaining skills in digital mapmaking and learning about how they can apply them in their field of road and transport engineering. In addition, they report that the laptop has been very helpful in every aspect of their transition to life in the US – including job searches, resume preparation, preparing for driver’s permit exams, participating in Zoom meetings, and others.

Saadiyo, a learner at a Literacy Minnesota-run learning center, wasn’t able to access remote classes because the family only had one computer, and her kids needed to use it for school. Literacy Minnesota was able to provide her with a device, but she needed help setting it up, connecting it to wifi, etc. The digital navigator configured the device with preset bookmarks Saadiyo needed for class, delivered the laptop to her, and walked her through set up, made sure the internet was connected, and walked her through how to find the tabs she needed to attend class. Now Saadiyo’s children aren’t the only ones in the family able to access education!

JoBeth, Sitting Bull College

JoBeth, a learner at Sitting Bull College, is a mother of 5 children trying to obtain her GED so that she can go to college. She never had the opportunity to work on her computer skills. “I never really knew how to work a computer until I stepped into the GED program.” With the help and support from a digital navigator at Sitting Bull College, Mariya learned some basic skills to use Word and other fundamental but critical skills to succeed in college. “I was never given a computer to learn how to use it, so I am grateful for this program to teach me the things I need to know and how to use technology.”

Latika, Byte Back

“Thank you for your sponsorship of the Digital Navigator Program at Byte Back which I am honored to be part of. My experience as a Digital Navigator has been great! I’m able to leverage the knowledge I’ve learned under the excellent instructors to assist Byte Back with entry-level IT tasks. Throughout the program, they’ve offered various opportunities to work on laptops, collect outstanding equipment, troubleshoot student tech issues, provide technical training to DC seniors and so much more. I hope to use my experience as a Digital Navigator to land a permanent Help Desk role and further hone my technical customer service skills. Thus far this program has proved to be an invaluable one and I’m so grateful for it.”